Environmental impact assessments and the Sihanoukville building collapse

Early in the morning of June 22, disaster struck Sihanoukville as a seven-story condominium building under construction collapsed. According to survivors, around 60 construction workers were on-site, some with their families sleeping.1 The collapse has killed 28 people and injured 25, and led to the resignation of Yun Min, Preah Sihanouk Provincial Governor and the firing of Nhim Vanda, Deputy Director of the National Committee on Disaster Management.2 Four people, including three Chinese nationals and the Cambodian landowner have been arrested and are expected to be tried in court for involuntary manslaughter.3 Media outlets from around the world are covering the story, bringing global attention to the dangerous working conditions for Cambodia’s construction workers and the rapid pace of development in Sihanoukville.4

A rescue team carries out a wounded worker from a collapsed building in Sihanoukville, Cambodia June 24, 2019. Reuters.

The local authorities reported that the building owners did not comply with construction codes and did not have a permit, but continued to construct the building anyway. 5 The authorities had previously warned the owners twice and tried to stop construction, but the owners did not cooperate.6 Local residents said that they feared that it was only a matter of time before something like this happened, because buildings in the area are built so quickly without any central planning or controls on development.7 The specific cause of the collapse has not yet been identified, but it is clear that the developers did not follow the construction laws and the local authorities were unable to effectively monitor them.8

In light of this tragedy, it is clear that greater accountability of the construction industry is needed. Regulatory frameworks do exist including the Law on Investment, the Law on Construction, construction codes published by the Ministry of Land Use, Planning, and Construction and most importantly the development of an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). EIAs are a tool that provide an important method of over site by the authorities in the interest of public safety to understand and ensure mitigation of the impact from development projects in the country. They are assessments that should be carried out prior to the commission of a project to critically evaluate the potential risks and harm and explore mitigation options if any for the project. Aspects of the project’s implications upon the environment, social value and economic gains are tested with stakeholders including the public to ensure that the project merits implementation. This document helps authorities closely monitor the project to ensure that the investors are upholding the conditions stipulated in the contract and EIA. However, the regulations that govern EIAs have not been updated in some time, and the process can be confusing to understand.

The two other laws covering foreign investment and building standards are the Law on Investment, amended in 2003, and the Law on Land Management, Urban Planning, and Construction, passed in 1994. The Law on Investment treats foreign and Cambodian investors equally, and encourages them to invest in “Qualified Investment Projects” which receive favorable tax and export benefits.9 The only real limit imposed is that foreign investors cannot own land in Cambodia.10 Additionally, the law provides a number of incentives to attract developers to Cambodia but puts no limits on the fields they can invest in, the amounts they can invest, or the responsibility they bear for any accidents or damages caused by the projects they invest in.11

The government exercises more control over the construction industry through Sub-Decree 86 on Construction Permits. All construction projects, with a few narrow exceptions, must have a construction permit.12 A committee within the Ministry of Land Use and Planning reviews the permit application and architectural drawings and must ensure that any proposed construction conforms with the master land use plan established by the provincial government.13 Approved permits must be publicly displayed at the construction site, and developers are not permitted to begin construction before the permits are delivered.14

Sub-Decree 86 does allow the government to hold developers responsible for the effects of their work, but doesn’t provide any clear standards for what would qualify as beneficial or harmful development. As seen in the Sihanoukville building collapse, there are also problems with enforcing the permitting requirement. The law does not provide a clear punishment for people who build without a permit, and only allows the authorities to suspend work at the site if the builders are in violation of their permit.15 The EIA process provides a much stronger method for the government to hold developers accountable. It requires significantly more public participation than the construction permitting process, requires developers to clearly indicate what their safety and environmental mitigation plans are, and has real enforcement mechanisms that hold the owners of a project liable through significant fines or imprisonment.16 These requirements allow the public to ask questions of the developer and inquire into their plans for worker safety and the integrity of the building design.

The Environmental Impact Assessment process

Chapter III of the Environment Law of 1996 is the main law governing environmental impact assessment reports, along with several sub-decrees. EIA reports are produced by the project developer and reviewed by the Ministry of the Environment, who examine the reports and provide recommendations to the project developer. After the MoE’s review, the Royal Government uses the report to determine whether or not to approve that project. Although the process is managed by the project developer and the government, open and prior public consultation is an internationally recognized practice of all EIA developments and this is no different under Cambodia laws. Public input is at the heart of EIA processes as it allows public constituents to provide inputs into the merits of the project and critically evaluate public service benefits.

The Royal Government has been working on a new Environmental and Natural Resources Code that would update and reform existing law. The new law was first proposed in 2015, and is still being drafted, so the old processes are still in place. The new Code would update the Environmental Impact Assessment process significantly. It introduces an EIA unit in the Ministry of the Environment to take responsibility for issuing permits and monitoring projects connected to the EIA process.17 They are also responsible for establishing a review committee made up of experts in the fields of construction and sustainability who will assess the viability of proposals in EIA reports. Officials of the EIA unit would also have the authority to provisionally postpone activities or close project sites if the project developer does not comply with the law.18 The Code would also adopt the use of Strategic Environmental Assessments and Risk Assessments as additional tools to monitor development projects. These Assessments are carried out by the Ministry of Environment, who would gather the data independently of the developers, and would make the reports publicly available.19

Currently, there are various sub-decrees that govern the developments of EIA procedures for different projects, but the 1999 Sub-Decree No.72 on the Environmental Impact Assessment Process, provides the specific provisions for how EIAs are to be carried out. The objectives of this sub-decree are to lay out the processes for performing an EIA, which building projects the EIA applies to, and to emphasize the importance of public participation in the EIA process. The sub-decree only applies to larger construction projects in the fields of industry, agriculture, tourism, and infrastructure.20 In Annex 1, it specifies that any building with a height above 12 meters or with a floor area greater than 8,000 m2 falls under the sub-decree no. 72, which mandates an EIA report produced prior to receiving government approval.21 Developers constructing a seven-story building, like the one involved in the Sihanoukville disaster, should have been required to produce an EIA report prior to commissioning and implementation.

However, the Sub-Decree provides an exception clause for “special-case” projects whereby the Royal Government can choose to approve a project without development of an EIA or oversite by the Ministry of Environment. Similar language is included in the new draft Environmental Law, with no standards for what constitutes a special-case project nor transparency of which projects have received this status.

Requirements under existing law

The regulations mandate that the developer produces an EIA report that is submitted for review to the Ministry of the Environment. Usually, the project developer will hire a private consulting firm to produce the report according to Ministry guidelines. An initial EIA report is produced that covers the physical, biological, and socio-economic environment of the site, and is based on existing secondary data.22 The MoE has 30 days to review the report, make findings and provide recommendations to the project owner.23 For projects that the MoE decides do not pose a threat to the local environment and communities, an initial EIA report is sufficient for project approval. Initial reports are often rapidly conducted, less detailed and often not accurate enough to base a decisions upon.24

If the MoE determines the project could pose a threat to natural resources, the ecosystem, the health of the local community or public welfare in general, the project owner will be requested and responsible for conducting a full EIA report. A full report launches an assessment that is conducted based on primary data collected from the project site. When the MoE receives this report, they have another 30 days to review it and provide recommendations. If the MoE fails to respond within that this timeframe, it is then assumed that the project is approved.25 Existing laws do not specify that the project owner has to comply with the recommendations made by the MoE. Although, the Royal Government has the final approval to issue the developer a license, regardless of if the MoE decides not to approve the EIA report.

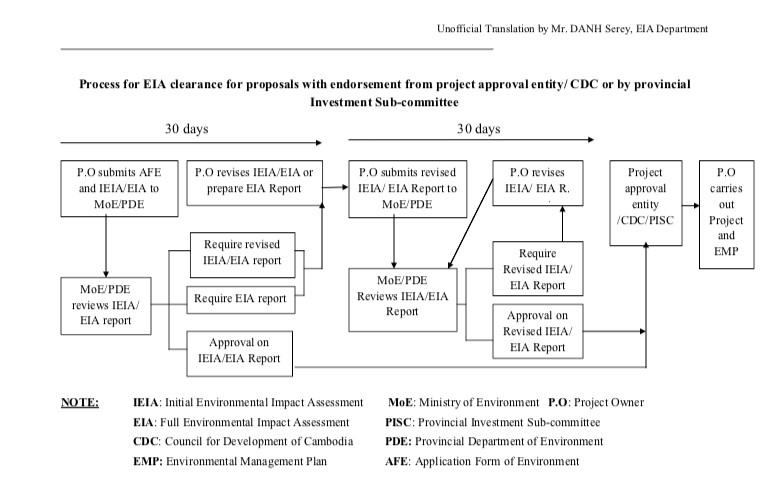

Figure 1: Outline of the EIA Process, taken from Prakas 376.

The specific requirements for the EIA report are determined by Prakas 376 on General Guideline for Developing Initial and Full Environmental Impact Assessment Reports of the MoE, published in 2009. The Prakas goes into minute detail of what is required for an EIA report to be satisfactory. The project owner must do a complete analysis of the existing environment and describe the project’s potential environmental, economic, and social impacts.26 When performing this analysis, they must also specify how the proposed project may affect local communities and what will be done to mitigate any negative effects. The developer must also make sure that the project will not violate several other sub-decrees establishing pollution standards. These include the Sub-Decree on Water Pollution Control, the Sub-Decree on Solid Waste Management, and the Sub-Decree on Air Pollution and Noise Disturbance.

In 2012, the Ministry of Environment in partnership with the NGOs Forum on Cambodia produced a guidebook on EIAs in Cambodia.27 The guidebook summarizes the laws and procedures for preparing an EIA report that were in effect in 2012, and because the draft Environmental Code is not yet in place the handbook is a useful tool for understanding how the Ministry of Environment handles EIA reports. The handbook specifies that every EIA report should make a determination on the type of impact a project will have, predict the scale and scope of that impact, and determine impact mitigation measures. The developer who proposes the project is always responsible for mitigating the environmental effects of that project.28 The handbook also specifies that the Ministry expects project owners to spend at least 3 months gathering data for initial EIA reports and at least 6 months for full reports.29

Public participation

Both the Environmental Law and Sub-Decree 72 emphasize that public participation in the EIA is an important part of the process, and that public concerns and input should be taken into account when planning development projects. Prakas 376 also specifies that as part of the EIA report, the developer should describe in detail how the public has been consulted and how public input has been integrated into the project. The Prakas does not give specific instructions for how to consult with the public, but the review of each EIA report at the ministerial and provincial level each should involve multi-stakeholder meetings where the public and other stakeholders can comment on the project.30

In 2016, the Ministry of the Environment released updated guidelines for public participation in the EIA process. The guidelines elaborate on the principles of public participation and the specific methods that should be used to involve the public in the EIA process. These guidelines emphasize the importance of providing all members of the public, especially women and indigenous communities, with access to the decision making process and effective remedies to environmental disputes.31 The guidelines specify the particular steps where public participation should occur and details how the public should be involved at each step. These steps are:

- Project screening;

- Project scoping,

- Preparation of the EIA Report and EMP,

- Reviewing and assessment of EIA report;

- Approval or Refusal of EIA Report;

- Construction, operation and project monitoring and compliance.32

At all steps the level of public participation expected is at least to inform or consult with the public.33 Additionally, depending on the scale of the project at least one public meeting should be held that allows the public to provide comments to the project developer and government officials.34 For larger projects, more public meetings during the project scoping stage should be held.

Monitoring and enforcement

After a project is approved by the Royal Government, the EIA is used as part of the government’s monitoring of the project. The project developer should begin to implement mitigation and management activities specified in the EIA within 6 months of approval.35 The MoE is responsible for monitoring all projects from the beginning of construction, through the operation and the closure of every project. They should ensure the project developers follow the mitigation and safety measures agreed to in the EIA report. Every project should be monitored both internally by the project manager and externally by the government, NGOs, and the local community.36 The developer should keep the public informed throughout the construction and operation of the project of potential impacts to the community.

If a Project Owner fails to comply with this process or provides false information during the EIA process, they will be in violation of the Environmental Law and could face legal penalties. The MoE can cooperate with other relevant institutions to terminate the project owner’s activities in connection with the project. Additionally, any official who acts negligently or violates the process is subject to administrative punishment and legal penalties.37

Impact of the draft Environmental Code

Beginning in 2015, the government began drafting a new Environmental and Natural Resources Code that would significantly update existing environmental laws. The New Environmental Code is significantly more detailed and comprehensive than the current Environmental law. Currently, the laws and regulations addressing environmental concerns in Cambodia are scattered through a number of different laws and sub-decrees, but the new law would gather all relevant codes in one document. It also makes public participation a priority, and that all information on these issues should be widely and publicly available “in a manner that maximizes the opportunity for public participation.”38 Anyone has the right to request information from relevant ministries or institutions, and all project participants are required to disclose all relevant information, although the manner of disclosure will be determined by each ministry.39

Under the draft code, any activity or project that may have a significant environmental impact must produce a risk assessment to predict what that impact will be and how to mitigate it.40The new code is intended to strengthen the review and monitoring process, and will create an Expert Review Committee that will review every project and allow independent experts to provide their input.41 No date has been announced for the implementation of the new code, but it has the potential to significantly improve the government’s ability to monitor construction projects and enforce laws for the safety of the public. While the current EIA process needs to be improved, environmental impact reports are becoming more common, and are being recognized as an important tool to monitor and control the rapid and potentially unsustainable development in Cambodia.

Comparing Cambodia to international EIA standards

Globally, EIA reports are regarded as a key planning tool for understanding the impact of large-scale development projects and controlling the development of needlessly destructive projects before they start.42 EIAs should systematically assess the entire project and consider every aspect of how the project will affect the surrounding community and ecosystem. The countries considered to have the strongest EIA policies are the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the Netherlands.43 In these countries, the public is consulted early in the planning stages and multiple development alternatives allow planners to decide on the least harmful method of achieving that country’s development goals. These countries also take into account the cumulative effects of approving many projects. Even if one project will not have a significant environmental impact, these countries consider how that project will add to the total impact of all approved projects. Recently, the global community has been trending towards using EIAs for all development projects, not just major ones, and the EIA process is increasingly considered a necessary part of sustainable development at the national level.

Cambodia’s EIA process is similar to its Southeast Asian neighbors, but lacks some procedures that are used in the best performing countries to ensure EIAs are an effective and valuable part of the planning process.44 Cambodia’s level of public participation in the EIA process is average for the region, but low globally. Cambodia’s law makes the EIA report public, but does not specify that supporting documentation must also be public, while most countries require this. Also, while Cambodia only takes public input into account in the initial planning stage, other countries involve the public after project approval by allowing the public to report projects that fail to uphold their EIA agreement, supporting monitoring and enforcement efforts. One of the most important provisions used by the best performing countries is requiring planners to consider alternatives to the proposed development that would have less impact on the community. Cambodian law does not require this, which is a major weakness in Cambodian EIA process.45

Overall, there is significant room in Cambodian law for improvement to align with international standards, specifically in the consideration of development alternatives and post-approval monitoring of projects. Countries that strongly enforce EIA agreements have seen safer and more sustainable building practices and more public accountability from developers.46 When governments rely on EIA reporting, they have acknowledged that environmental sustainability encourages social and economic security, and encourage long-term stability over short-term economic gains.

Click here for more information about Environmental Impact Assessments

Click here for a list of publicly released EIA reports

References

- 1. Martin Farreer. “Five Chinese charged as toll in Cambodia building collapse rise to 28”. The Guardian, 25 June 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/24/chinese-builders-arrested-as-toll-in-cambodia-building-collapse-rises-to-24

- 2. “Cambodian sacks minister over building collapse as toll rises to 28”. Channel News Asia, 24 June 2019. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/cambodia-sacks-minister-over-building-collapse-as-toll-rises-to-11655268

- 3. Khy Sovuthy.”Four to be sent to court over deadly building collapse”. Khmer Times, 24 June 2019. https://www.khmertimeskh.com/617188/four-to-be-sent-to-court-over-deadly-building-collapse/

- 4. “Cambodia building collapse: Two pulled alive from rubble”. British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) News, 25 June 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-48741234

- 5. Paul Eckert. “15 Dead in Collapse of ‘Illegal’ Chinese-owned building in Cambodia’s Sihanoukville”. Radio Free Asia, 22 June 2019. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/cambodia/sihanoukville-collapse-06222019150251.html

- 6. Long Kimmarita.”Sihanoukville building collapse death toll rises to 19″. The Phnom Penh Post, 24 June 2019. https://www.phnompenhpost.com/national/sihanoukville-building-collapse-death-toll-rises-19

- 7. “Cambodian sacks minister over building collapse as toll rises to 28”. Reuters, 24 June 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-cambodia-construction-accident/cambodia-sacks-minister-over-building-collapse-as-toll-rises-to-28-idUSKCN1TP0ZJ

- 8. Long Kimmarita.”Sihanoukville rescue operations end, inquiry set to begin”. The Phnom Penh Post, 26 June 2019. https://www.phnompenhpost.com/national/sihanoukville-rescue-operations-end-inquiry-set-begin

- 9. Law on Investment of the Kingdom of Cambodia, Article 8.

- 10. Law on Investment of the Kingdom of Cambodia, Article 16.

- 11. Sciaroni & Associates, Doing Business in Cambodia, 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20200704191233/http://sa-asia.com:80/sa/category/our-doing-business-guides/

- 12. Sub-Decree 86 on Construction Permit, Article 2.

- 13. Sub-Decree 86 on Construction Permit, Article 7.

- 14. Sub-Decree 86 on Construction Permit, Article 12.

- 15. Sub-Decree 86 on Construction Permit, Article 20.

- 16. Sub-Decree 72 on Environmental Impact Process.

- 17. Environmental and Natural Resources Code of Cambodia, Revised 9.1th Draft (2017), Article 95.

- 18. Environmental and Natural Resources Code of Cambodia, Revised 9.1th Draft (2017), Article 99.

- 19. Environmental and Natural Resources Code of Cambodia, Revised 9.1th Draft (2017), Article 66 & 73.

- 20. Sub-Decree No.72 on the Environmental Impact Assessment Process. Chapter 1, Annex 1.

- 21. Sub-Decree No.72 on the Environmental Impact Assessment Process, Annex 1.

- 22. Prakas No.376 on General Guideline for Developing Initial and Full Environmental Impact Assessment Reports, Article 10.

- 23. Prakas No.376 on General Guideline for Developing Initial and Full Environmental Impact Assessment Reports., Annex 1.

- 24. Prakas No.376 on General Guideline for Developing Initial and Full Environmental Impact Assessment Reports, Annex 1.

- 25. Sub-Decree No.72 on the Environmental Impact Assessment Process, Article 18.

- 26. Prakas No.376 on General Guideline for Developing Initial and Full Environmental Impact Assessment Reports., Annex 1.

- 27. Guidebook on Environmental Impact Assessment in the Kingdom of Cambodia, Ministry of Environment, Environmental Impact Assessment Department, 2012

- 28. Guidebook on Environmental Impact Assessment in the Kingdom of Cambodia, Ministry of Environment, Environmental Impact Assessment Department, 2012. Chapter 3.2e.

- 29. Guidebook on Environmental Impact Assessment in the Kingdom of Cambodia, Ministry of Environment, Environmental Impact Assessment Department, 2012. Chapter 3.2f.

- 30. Prakas No.376 on General Guideline for Developing Initial and Full Environmental Impact Assessment Reports, Article 11 and 12.

- 31. Guideline on Public Participation in Environmental Impact Process, Ministry of Environment, Environmental Impact Assessment Department, 2016.Chapter 1.3.

- 32. Guideline on Public Participation in Environmental Impact Process, Ministry of Environment, Environmental Impact Assessment Department, 2016. Chapter 1.5.

- 33. Guideline on Public Participation in Environmental Impact Process, Ministry of Environment, Environmental Impact Assessment Department, 2016. Chapter 1.6.

- 34. Guideline on Public Participation in Environmental Impact Process, Ministry of Environment, Environmental Impact Assessment Department, 2016. Chapter 3.2.

- 35. Guidebook on Environmental Impact Assessment in the Kingdom of Cambodia, Ministry of Environment, Environmental Impact Assessment Department, 2012. Chapter 3.2h.

- 36. Guideline on Public Participation in Environmental Impact Process, Ministry of Environment, Environmental Impact Assessment Department, 2016.Chapter 3.6.

- 37. Sub-Decree No.72 on the Environmental Impact Assessment Process, Chapter 7.

- 38. Environmental and Natural Resources Code of Cambodia, Revised 9.1th Draft (2017), Article 6.

- 39. Environmental and Natural Resources Code of Cambodia, Revised 9.1th Draft (2017), Article 32.

- 40. Environment and Natural Resources Code of Cambodia, Revised 10th draft (2018).

- 41. Environment and Natural Resources Code of Cambodia, Revised 10th draft (2018).

- 42. Jennifer C. Li. Environmental Impact Assessments in Developing Countries: An Opportunity for Greater Environmental Security? Foundation for Environmental Security and Sustainability, 2008.

- 43. Ibid. p2.

- 44. PACT. Environmental Impact Assessment Comparative Analysis In Lower Mekong Countries. 2015.

- 45. PACT. Environmental Impact Assessment Comparative Analysis In Lower Mekong Countries, p 39. 2015.

- 46. Li, Environmental Impact Assessments, p 2.