Rice Farmer in Cambodia. Photo by Khem Sovannara, ILO in Asia and the Pacific, taken on 12 July 2007. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Social Land Concessions (SLCs) are intended to provide to the landless or land-poor land on which to establish residences and/or generate income through agriculture. Despite its pro-poor intention, the SLC initiative has faced challenges, with activists, land rights groups and communities claiming that SLCs have generated new land disputes and increased deforestation.1

Landlessness in Cambodia

Various studies have observed that the number of landless Cambodians is rising, though there are no up to date official statistics available on this issue. A 2014 study conducted by the Cambodian Development Resource Institute (CDRI) found that 28 prcent of its survey sample was landless between 2004 and 2011, and 47 percent held less than half a hectare of land – the minimum required for subsistence.2 Recognizing the problem, the Cambodian government has developed and implemented a system to redistribute state land to the land-poor.

Policy

In 2002 the Cambodian government adopted an interim land policy, which, among other objectives, aimed to promote land distribution with equity.3 The government issued a declaration on Land Policy in 2009, and re-asserted its aim to distribute land to those in need. Under its Land Distribution Sub-Sector Program, the government aims to distribute land through social land concessions “in a transparent and equitable manner in response to the needs for land of the people”, focusing in particular on the poor, disabled soldiers, and families of deceased soldiers.4

Legal framework

The 2001 Land Law formally established SLCs, and, with Sub-decree No.19 on Social Land Concessions, set out the conditions under which SLCs can be granted and used. The Land Law states that an SLC is a land concession responding to a social purpose “which allows beneficiaries to build residential constructions and/or to cultivate lands belonging to the State for their subsistence.”5 During the concession period, the rights of a concessionaire are similar to those of an owner. Importantly, they do not have the right to transfer the land to any other person.

SLCs must be issued by a specific sub-decree prior to the occupation or cultivation of land commencing and must be registered with the Ministry of Land Management, Urban Planning and Construction (MLMUPC).6 The Land Law and sub-decree state that SLCs may only be granted on state private property.7

Sub-decree No.19 sets out the specific mechanisms for granting SLCs. In addition to the land-poor and disabled soldiers, SLCs may be granted to provide land for families who have been displaced by public infrastructure development or affected by natural disasters; demobilized soldiers and families of soldiers who were disabled or died in the line of duty; facilitating economic development; and facilitating economic land concessions by providing land to plantation workers.8

Depending on the nature of the SLC, it may be initiated at the local or the national level.9 Local SLCs may be requested by citizens or civil society organizations working on behalf of communities,10 whereas a ministry or other government institution must initiate a national level SLC.11 After a SLC plan is announced, local people may submit applications evaluated by a District Working Group.12

In order to be eligible to apply for an SLC, individuals must:

- be a Cambodian national with legal capacity to own land;

- meet the financial criteria established by prakas of the Ministry of Social Affairs, Labour, Vocational Training and Youth Rehabilitation;

- not own or possess other land equal to or greater than the size limitations for SLCs; and

- be ready, willing and able to participate in the SLC program, in accordance with the approved SLC plan.

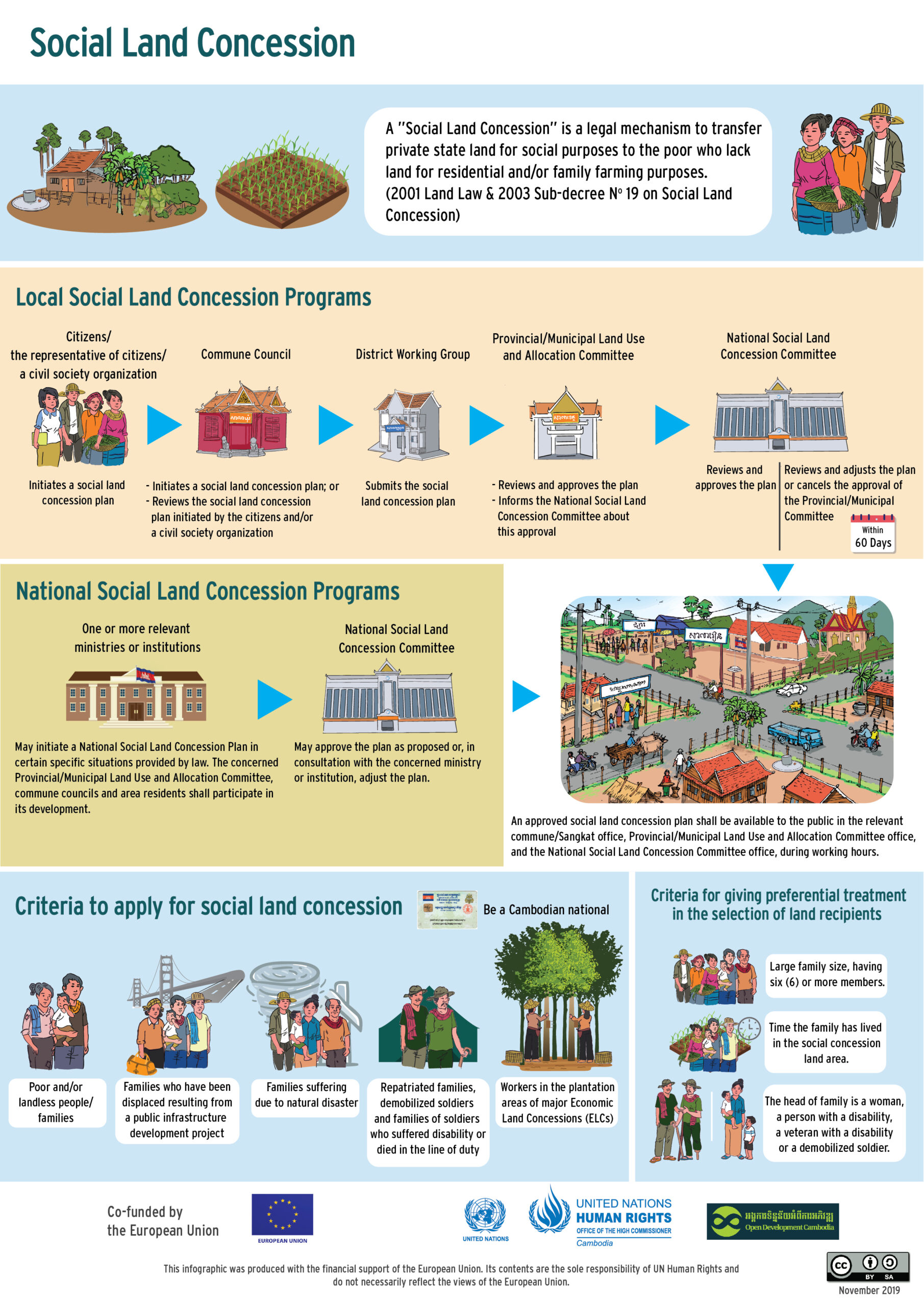

This Social Land Concession infographic was coproduced by Open Development Cambodia (ODC) and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in Cambodia, funded by the European Union. The infographic was published in November 2019. License under CC BY-SA.

SLCs can be granted as residential land or agricultural land, or some combination of the two.13 Every SLC recipient must sign an agreement with the granting authority. Absent an existing residence, the recipients of residential land must build a permanent shelter within three months and a family member must reside permanently on the land for at least six months each year. Recipients of an agricultural SLC should start to cultivate the land within twelve months of receiving it and continue to use it thereafter. After five years of continuous occupation or use, the SLC recipient has the right to request title to the land. During the first five years, the land recipient may not transfer SLC land to any other person or entity, and if the recipient fails to meet the conditions, the land may be returned to the state and reallocated.14

Progress in social land concession distribution

Progress towards the target of providing residential and agricultural SLCs to a minimum of 10,000 landless households by 2010 was slow.15 As of June 2010, SLCs had been granted to 2,595 families.16 The NSDP 2014-2018 states that, as of the end of 2013, 31,000 households received land under the SLC program, 15,000 of whom were poor civilians.

In a number of concessions, families who have lived on their land for five years have received title. In March 2018, for example, the Ministry of Land Management, Urban Planning and Construction issued titles to 776 families living on social land concessions in Santuk district of Kampong Thom province. A total of 1,351 titles were issued for the plots of land – each family received a 30 x 40 metre plot for housing and 1.5–3 hectares for farming.17

While the amount of land granted as SLCs is in the tens of thousands, the amount of land granted as ELCs is upwards of 1.2 million hectares.18 To address a lack of land availability for SLCs, the government has indicated that it aims to find and identify land that is unused, available from cancelled ELCs, or available through demining. It also seeks to develop a SLC and ELC partnership policy and strengthen the overall SLC mechanism.19

A key intervention for increasing the coverage of SLCs is the World Bank and GIZ funded Land Allocation for Social and Economic Development (LASED) project. Beginning in 2008, the project aims to improve the process for identification and use of state lands transferred to the land-poor. Conflicting reports exist concerning the number of SLCs granted through LASED. The NSDP for 2014-2018 stated that, as of July 2014, 5,000 households benefited from the project, while the World Bank reported in December 2014 that 3,148 households received land from LASED. Additionally, the World Bank and GIZ reported strong success and resettlement rates, with significant improvements in food security and reductions in poverty.20

Contrastingly, a June 2015 NGO report determined that rates of resettlement on SLCs were less than 50 percent and only 41 percent of agricultural land had been cultivated due to poor land quality, insufficient capacity, and conflicts over land.21 The reported result is that agricultural plots are insufficient to support adequate cultivation, resulting in the persistence of food insecurity. Further, it was claimed that land tenure security had not improved among grantees as no titles had yet been awarded despite the process commencing in 2013.22

There have also been concerns that mechanisms to ensure the social and environmental sustainability of SLCs are not always implemented. In 2008, an NGO position paper raised concerns that locally initiated SLCs were being granted illegally in the absence of adequate environmental and social assessments.23

Land conflicts resulting from SLCs

According to NGO reports, the process of allocating SLCs have been linked to land conflicts across the country. A report by ADHOC noted that in 2012 the government granted 38 SLCs – double the number granted in 2011 – covering 100,790 hectares.24 Out of these 38 SLCs, the study found that 13 resulted in land conflicts. Since then, the number of SLCs is reported to have increased sharply,25 yet the process of their allocation continues to cause concerns.26 In 2015, land conflicts in SLCs are continue to be reported in the national press.27

Conflicts are reported to arise when SLCs have been granted in areas where people already reside. CCHR reported a case in Kulen district, Preah Vihear province, where the government allocated a 5,557 hectare plot as an SLC for 160 disabled solders.28 However, the area designated an SLC was already occupied. It was alleged by400 villagers living on the site that authorities destroyed their dwellings and farmland after their property was converted to an SLC.

It has also been reported SLCs can weaken the tenure rights of potential beneficiaries. A 2013 study in Kratie province found that 130 families were evicted from an SLC because their tenure commenced after 2001 and, as a result, authorities deemed them to be illegally encroaching on state land.29

In other cases, powerful individuals are reported to have used SLCs as a mechanism to grab land from poor communities. ADHOC reported a case in ChaomKsan district, Preah Vihear province, where an NGO run by a one-star general was granted an SLC over an already populated area.30 The SLC was granted on the premise that disabled families would be settled there by the NGO. Instead, the villagers claimed that the land covered by the SLC was sold by the NGO for profit. The community members alleged that they had harassed by the NGO resulting in some leaving their land without any compensation.

Social land concessions in urban areas

SLCs have been used as a tool to upgrade areas of low-income, unplanned housing in urban areas. The two best-known examples are Dey Krahorm and Borei Keila in Phnom Penh, both of which resulted in land conflicts. Dey Krahorm was a low income community that, according to authorities, consisted of 1,465 households living on a4.7 hectare site(these figures were disputed by community members) in the central Phnom Penh commune of Tonle Bassac. According to NGO reports, the land was thought to be state private, although which state entity administered the land was not clear.31 However, some NGO observers considered the community to have strong claims of ownership under the 2001 Land Law.32

In 2003, the government declared that it would convert the area from state property to an SLC as part of a land-sharing development plan.33 A portion of the land was to be allocated to a private company and a portion allocated to residents. The private company would provide modern on-site housing units for all residents in return for a portion of the land.

The land-sharing plan did not proceed as envisaged in agreements. A group purporting to represent the community signed a new agreement with the company that differed in several ways to the original deal. The new agreement stipulated that the company would house the community in a site 20km away from Dey Krahorm in a peri-urban district.34 In addition, the company would be granted the whole Dey Krahorm land parcel.

On learning of the agreement, residents asserted that they were neither consulted about nor agreed to such a deal. According to NGO observers, the agreement was invalid under Cambodian law because the community representatives did not have the right to sell the land on behalf of the community.35 The legality of the agreement was challenged in court. However, the court ruled that it was binding. As a result, the community was removed in a violent eviction.

NGOs observers noted that there were many problematic aspects of the Dey Krahorm SLC.36 One of the most significant related to implementing an SLC in an area that was already occupied and where residents may have met the criteria for legal possession and, therefore, ownership titles. Rather than securing residents’ property rights with land titles, the SLC enabled the transfer of their land from residents to a private company.

The issues that occurred in Dey Krahorm have also been present in other SLC land-sharing interventions in Phnom Penh. Dey Krahorm was one of four low-income settlements in Phnom Penh to be designated an SLC as part of a 2003 government settlement upgrading programme. Three of these ended in the beneficiary communities being evicted and in the fourth site – Borei Keila – a protracted land conflict has resulted in a proportion of the residents re-housed on site.37

Related to social land concessions

- Concessions

- Land, housing rights and evictions

Last updated: 30 March 2018

References

- 1. May Titthara. 2014. “Scepticism Over Social Land Grants.” Phnom Penh Post, 3 March. http://www.phnompenhpost.com/national/scepticism-over-social-land-grants See also LICADHO. 2015. “On Stony Ground: A Look into Social Land Concessions.” http://www.licadho-cambodia.org/reports/files/208LICADHOR eport-LASEDSocialLandConcessions2015-English.pdf.

- 2. Chan Sophal. 2008. “Policy Brief: Impact of High Food Prices in Cambodia.” CDRI, 2. https://cdri.org.kh/wp-content/uploads/HFPsurveyPME.pdf .

- 3. Council of Ministers. 2001. “Statement of the Royal Government on Land Policy.” May 2001. Royal Government of Cambodia. 2002. “Interim Paper on Strategy of Land Policy Framework.” Prepared by the Council for Land Policy.

- 4. Council of Ministers. 2009, Declaration of the Royal Government on Land Policy, 1 July 2009.

- 5. Land Law 2001, Article 49.

- 6. Land Law 2001, Article 53.

- 7. Land Law 2001, Article 58.

- 8. Royal Government of Cambodia (2003). “Sub-decree No.19 on Social Land Concessions.” 19 March 2003, Article 3.http://www.cambodiainvestment.gov.kh/sub-decree-19-on-social-land-concessions_030319.html.

- 9. Ibid., Chapters 2 and 3.

- 10. Ibid., Article 5.

- 11. Ibid., Article 7.

- 12. Ibid., Articles 12 and 13.

- 13. Ibid., Article 15.

- 14. Ibid., Articles 18.

- 15. National Strategic Development Plan 2006-2010. 27 January 2006: 60. http://www.paris21.org/sites/default/files/cambodia-nsdp-2006-2010.pdf

- 16. National Strategic Development Plan Update 2009-2013.” 30 June 2010: 35, 128. http://www.gafspfund.org/sites/gafspfund.org/files/Documents/Cambodia_6_of_16_STRATEGY_National_Strategic_%20Development_Plan.NSDP__0.pdf.

- 17. Pech Sotheary 2018. “Land titles granted to nearly 800 families”, Khmer Times, 30 March 2018. http://www.khmertimeskh.com/50269438/land-titles-granted-to-nearly-800-families/ Accessed 30 March 2018

- 18. Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. “Economic Land Concessions: Overview.” Accessed 3 July 2015. http://www.maff.gov.kh/elc/.

- 19. National Strategic Development Plan: 2014-2018. http://www.maff.gov.kh/គោលនយោបាយ/ 1240-nsdp-2014-2018-en.html

- 20. “World Bank Allocation for Social and Economic Development (LASED).” World Bank. Accessed 24 June 2015. http://www.worldbank.org/projects/P084787/land-allocation-social-economic-development?lang=en. “Land allocation for social and economic development – LASED.” GIZ. 2014. Accessed 24 June 2015. http://giz-cambodia.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/FactSheet-LASED-140529.pdf.

- 21. LICADHO. 2015.

- 22. Ibid.

- 23. NGO Forum on Cambodia. 2008. “NGO Position Papers on Cambodia’s Development in 2007-2008.” November 2008: 66. https://data.opendevelopmentmekong.net/dataset/ngo-position-papers-on-cambodia-s-development-2007-2008/resource/c2f6a8b1-5082-454e-a949-aaf77b2969de/view/ba6cc1d1-8d9e-4537-9beb-33e89fb319d8

- 24. ADHOC. 2013. “A Turning Point? Land, Housing and Natural Resources Rights in Cambodia in 2012.” ADHOC: Phnom Penh.

- 25. S. Worrell. 2014.“Social Land Concessions Climb.” Phnom Penh Post, 31 January 2014. Accessed 25 October 2014, http://www.phnompenhpost.com/national/social-land-concessions-climb

- 26. LICADHO. 2015.

- 27. See, for example, Staff. 2015. “Armed Guards Forcibly Evict Residents from Village in Cambodia’s Kratie Province.” RFA. 9 April. http://www.rfa.org/english/news/cambodia/authorities-evict-villagers-in-kratie-04092015170819.html

- 28. CCHR. 2014. “Cambodia: Land in Conflict – An Overview of the Land Situation.” CCHR: Phnom Penh.

- 29. A. Neef, S. Touch and J. Chiengthong, 2013. “The Politics and Ethics of Land Concessions in Rural Cambodia.” Journal of Agri. Environ. Economics 26:1085-1103.

- 30. ADHOC. 2012. “Villagers from Kantuot Commune, ChoamKsan District Promised Action after Delivering Petition to Prime Minister.” Accessed 28 October 2015, https://www.adhoccambodia.org/villagers-from-kantuot-commune-preah-vihear-province-are-promised-action-after-delivering-petition-to-prime-minister/

- 31. LICADHO. 2008, Dey Krahorm Community Land Case Explained.” Phnom Penh: LICHADO.

- 32. BABSEA. 2009. “The Grand Theft of Dey Krahorm.” Accessed 23 October 2015, https://data.opendevelopmentcambodia.net/library_record/the-grand-theft-of-dey-krahorm

- 33. Council of Ministers Letter No. 875 Sar. Cho. Nor, 8 July 2003. “Request for policies for managing the social concession land for residential development for the poor communities in Phnom Penh capital.”

- 34. LICADHO. 2008, Dey Krahorm Community Land Case Explained.” Phnom Penh: LICADHO.

- 35. Land and Housing Working Group. 2009. “ Land and Housing Rights in Cambodia Parallel Report 2009.” Accessed 20 October 2015, http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/cescr/docs/ngos/CHRE_Cambodia_ CESCR42.pdf .

- 36. LICADHO. 2008. Dey Krahorm Community Land Case Explained.” Phnom Penh; LICHADO. BABSEA. 2009. “The Grand Theft of Dey Krahorm.” Accessed 23 October 2015, www.babcambodia.org/articles/docs/BABC%20-%20The%20Grand%20Theft%20of%20Dey%20 Krahorm.pdf.

- 37. P. Rabe. 2010. “Land Sharing in Phnom Penh and Bangkok: Lessons from Four Decades of Innovative Slum Redevelopment Projects in Two Southeast Asian ‘Boom Towns.’” Accessed 11 October 2015, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/event/Rabe.pdf